As a child, I loved drawing so much that I would lose all sense of time. But eventually, I had to let go of that dream. Years later, while working, an unexpected encounter led me back into a deeply fulfilling period of painting. Now, through art and quiet conversation, I hope to gently be alongside others and support their hearts.

Career Highlights

2010 — Studied Western-style painting under Kouichi Sumi; first submission and first acceptance into the City Exhibition

2011 — Accepted into the City Exhibition

2012 — Accepted into the All-Japan Art Salon Painting Grand Prize Exhibition; held a solo exhibition; accepted into the City Exhibition

2013 — Exhibited accepted work at the National Art Center, Tokyo; accepted into the City Exhibition

More than titles or credentials, I would be glad if you could see how art has been part of my life’s journey. If you’d like to know more, please read the full interview.

Part 1: “Beyond the Time I Couldn’t Paint” — Encountering Painting Again as a Way to Regain Myself

1. Childhood to Student Years: First Encounters with Art — “Behind the Mask, My True Feelings”

Since I was a child, art class was always my favorite. Drawing and making things felt purely fun, and in elementary school, I mostly drew manga-like pictures.

When I joined the art club in junior high, I began to try sketching and other forms of drawing, which made me want to paint even more. I especially loved works created with bold, vivid colors, like poster paints. One of my most memorable pieces was a painting of a “mask” I made in high school on a free theme. It was divided into bright colors, and even my teacher told me, “This is interesting.”

Looking back, I wonder why I chose to paint a mask. Perhaps it reflected the way I felt as a teenager. I often sensed that the faces people showed in groups weren’t their true selves. I, too, had always been the type to read adults’ moods and avoid expressing my emotions freely. I tried not to upset my parents by hiding my own feelings. Painting a “mask” may have been my way of expressing that discomfort and doubt.

In truth, I wanted to go to an art high school. But by then, preparations for a general academic track were already underway, and my parents said, “It’s too late to switch to an art course now.” My mother also told me, “You can’t make a living from art.” Even when I had asked in elementary school to attend a local painting class, she dismissed me, saying, “Art isn’t something you need lessons for.”

My dream had actually started much earlier. In kindergarten, I wanted to be a designer. I drew frilly costumes I saw on TV idols, as if dressing dolls on paper. I wasn’t good at sewing, but I was fascinated by designing — choosing colors and shapes.

Because I had grown up believing that “following others’ wishes is best,” I gave up on art and closed off my own feelings. Yet the desire to paint, hidden deep inside, never really disappeared.

2. Returning to Painting as an Adult: A Restart Sparked by Heartbreak — “You Can Paint” Opened the Path

As a working adult, painting vanished completely from my daily life. I sometimes visited museums, but I no longer picked up a brush myself.

The turning point came at age 30. After a painful breakup, I felt as though a hole had opened in my everyday life. My days became nothing more than commuting between home and the office. Wanting to change something, I confided in a friend. She reminded me, “Didn’t you love painting?” and introduced me to a painting class. It meant a lot that she had remembered how much I loved drawing.

The class was held above an art supply store, and people of all ages attended, from children to adults.

But within a month, I began to feel weighed down. Since the class was inside a supply shop, I was constantly encouraged to buy materials — “This paint is good,” “How about this one?” — which became stressful over time.

When I finally confessed my feelings to the teacher, he gave me an unexpected answer:

“I also run a class in my studio — why don’t you come there instead?”

He added, “When I saw your first painting, I thought, ‘Ah, this person can really paint.’” Those words stayed deeply in my heart.

That became the beginning of my daily life with painting once again.

At his studio, it was just the teacher, a 17-year-old high school art student, and me. In that unusual, intimate space, I spent about four intense years.

The teacher’s own workspace was next door, so I could see him working on pieces for exhibitions, even his behind-the-scenes process. It was the first time I had seen such large works — canvases over 100 size — up close. Watching the brushstrokes, the layering of colors, and the way a painting came to life was a precious experience. I could feel the true depth of what it means to paint.

3. Exhibitions and Large Canvases: Four Years of Self-Recovery — “Dormant Feelings Came Alive on a Big Canvas”

The passion for art, smoldering in my heart for years, was something I finally confessed to my teacher. Though my parents had once opposed it and I had turned away, I had never truly let it go.

After that, my teacher suggested I try submitting to public exhibitions.

Two or three months after joining, for my second painting, he decided — “It’s better to have a goal,” he said — that I should create my next work on a size 50 canvas (over one meter).

It was my first time painting on such a large canvas.

In that piece, a doll-like girl stood at the center among adults wearing many masks. Her expression was blank, her eyes teary, her hair white, her skin pale, her body half-exposed. Perhaps she represented myself at that time, drained of energy. That painting, my debut submission, was accepted.

Sadly, the piece no longer exists, but working on large canvases taught me a lot.

With small paintings, you can see the whole picture even while working up close. But on a size 50 or 100, you lose sight of the overall balance while focusing on details. Many times, I’d realize, “This color looks out of place,” only to find the harmony had already collapsed.

So my teacher often said:

“Paint, then step back.”

“Think about the composition before you start painting.”

If you simply follow your emotions with the brush, fixing it later becomes very difficult, wasting paint, time, and energy. Large works demand planning — carefully considering composition and colors before beginning.

With wide surfaces, the challenge is how to place colors in the blank spaces — the “intervals.” My works often ended up monotonous.

“Boring,” the teacher would often scold.

But each moment was still a dialogue with myself and with the work. Painting was an act of reclaiming myself.

4. Inspiration from New York: Transformation Through Seeing the Real Thing — “My Brush Changed After Experiencing Authentic Works”

As I continued painting, I began to strongly feel, “I want to see real paintings.” Around that time, I traveled to New York with a friend on a whirlwind 5-day, 3-night trip. We only visited two museums, but the experience was invaluable.

In overseas museums, you can view works extremely close-up, and photography is often allowed — something rare in Japan. With oil paintings, brushstrokes, layering, and textures can only be truly understood up close. I was overwhelmed by the raw power.

Immediately after returning, I went to class and began a new painting. My teacher remarked, “Something has changed.” He didn’t say exactly what, only that it had become “much better.” Those words still stay with me.

Our conversations were always more about impressions than technicalities.

Of course, things weren’t always smooth. Sometimes, after work, my paintings felt stiff or dull, and my teacher said so. My work mode had carried into the canvas. Still, having the goal of exhibitions kept me painting despite emotional ups and downs. It was fun.

I realized painting requires not only emotion but also composition, planning, and focus. Yet logic alone is not enough — without emotion and impulse, a painting won’t touch the heart. Balancing the two was the real challenge.

The simpler the composition, the harder it is. A single misplaced line can ruin the entire impression. The ability to notice such subtle dissonance — and the patience to correct it — makes all the difference.

These were experiences beyond money.

And every time, my teacher reminded me, “Train your eyes more.” Even paintings that look simple at first reveal complex layers and structures upon closer inspection.

Looking back, my teacher was strict. Watching him, I felt the toughness and discipline of living as an artist. With his heightened sensitivity, he never fit neatly into society’s framework — but he transformed that struggle into art. Witnessing that up close was an irreplaceable lesson. Still, I knew I could never go that far myself.

Part 2: “Living Again Through Painting” — Miscarriage, Commissioned Works, and Encounters with Spiritual Sensibility

1. Painting on Commission :The Surprise and Joy of Creating for Someone Else — “The words ‘Please paint for me’ changed the meaning of painting.”

After attending the atelier for about four years, I eventually graduated. During that time, I submitted works to several public exhibitions and even had the experience of being displayed at the National Art Museum. I was accepted in my third year, which became a major milestone for me.

I was 34 then — a time when I was also thinking about what kind of life I wanted as a woman. Immersing myself too deeply in painting made me worry I might neglect other aspects of my life. So I decided to step back and return to reality for a while.

Not long after I left the class, I encountered a new path.

One day, while chatting with my chiropractor, I mentioned that I was interested in psychology. He encouraged me, saying, “Even if it’s unrelated to your work, learning itself has value.”

That led me to study NLP, a program about psychology and communication, which I attended for about two years. Looking back, I think that learning is what now connects me to “painting for others” and “receiving feelings through dialogue.”

After that, I got married, had children, and moved away from study for a while. Talking about it now, I realize I’ve done quite a lot (laughs). In my 40s, I feel as though all of it is coming together.

During that time, I happened to join an online class held over Zoom, connecting from my parents’ home. On the wall behind me hung a large painting I had once made at the atelier — the piece of the “girl and masks.”

The lecturer was someone with a slightly spiritual sensibility, who spoke from a unique perspective blending quantum physics and other ideas. At the time I was struggling with work and joined hoping for change.

Seeing my painting through the screen, the lecturer asked, “Who painted that?” Then said, “You’re not painting now, are you? But you absolutely should. Please paint one for me.”

I was so surprised by those words. Hesitant, I replied, “Maybe I can do a small piece,” and accepted the commission. That was about six years ago.

It was pure joy to paint. No one had ever asked me so directly to “paint for them.”

I was told, “Please paint as you like.” So I thought of that person while creating. A few days after I mailed the finished piece, I received a message:

“When I opened the envelope and pulled out the painting, I couldn’t stop crying.”

That person was deeply sensitive and must have felt something profound. They told me over and over, “I’m so glad I asked you.”

I was moved that my painting could bring such joy. That moment became the start of painting for others.

The work was of the sea — I can’t recall whether it was sunrise or sunset, but it showed the sun rising or sinking into the ocean. Quiet yet filled with strong energy, that was the impression it carried.

2. Painting Life :Commissions, Loss, Emotion, and Prayer“When emotions are aligned, painting becomes prayer.”

I posted that painting on Facebook with the words, “I painted this for someone.” Soon after, someone else commented, asking me to paint for them as well.

That next client worked in IVF treatment. While thinking of them, the image of “the birth of life” naturally arose. I painted with that theme, titling it something like “The Moment Life Begins.”

The piece, a small samall size (about 20 cm), was finished in a day or two. Looking at their photo while sketching quickly in my notebook, images kept flowing.

When asked if I have spiritual sensitivity, I don’t talk about it much. But for me, when I look at someone’s photo while drawing, I feel as if I enter into their inner world.

I’ve never painted for someone I haven’t spoken with. Even online, I’ve always had at least one conversation first. Through words, their sensibility leaves an impression in me. Then when I see their photo, it triggers that memory, and I can naturally step into their presence.

I believe I can’t paint for someone unless my own emotions are steady. Energy flows into the painting, and I don’t want to hand someone a work infused with negative feelings.

As I continued, I found myself visiting shrines more often, sensing a kind of “connection with above.” During the time I stepped away from work, that sensitivity seemed to sharpen.

Naturally, I began painting dragons. I don’t literally “see” them, but I feel the presence of something like a dragon spirit. Some may call it imagination, but for me it’s real. And so I began painting them.

I’m not leaning toward any religion. But more than before, I’ve come to believe in the existence of the unseen. Painting, before I knew it, had become close to prayer.

3. A Turning Point: The Miscarriage Painting and the Pain That Changed My Life — “The Most Painful Experience Became My Greatest Work”

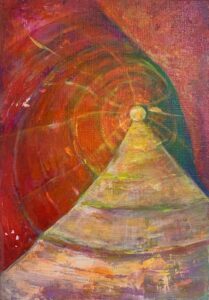

Rewinding a little, sometime after my first commission, I experienced a miscarriage. It was heartbreaking, both physically and emotionally, but I felt I needed to give that experience form.

That became this painting. I consider it part of my life itself, which is why I use it as my Instagram icon.

It reflects my memory and sensations on the operating table during the procedure.

Though under anesthesia, I felt myself floating, spinning through a red tunnel. My body descended, and just as I thought, “I’m about to touch the ground,” I suddenly heard voices:

“The anesthesia is wearing off.”

The doctor replied, “Just a little longer.”

I could hear sounds — perhaps the fetus and tissue being removed. Then suddenly, my body dropped, and I regained consciousness. “It’s over,” they said.

I wondered if, at that moment, I had been together with my child in the birth canal — perhaps I sensed the child’s soul.

It was the most painful experience of my life. Even now it hurts to recall. Yet I believe it had meaning, because here I am sharing it, hoping it may help someone.

Without that experience, painting might have remained just a hobby.

4. Encountering Washi and Japanese Expression — “Washi Leads Me Into the Depth of Japanese-Style Painting”

Another turning point was discovering washi paper as part of my expression.

It began while painting Mount Fuji. I wanted to create clouds, and happened to have washi on hand.

I had long been drawn to Mino washi and often bought it without knowing when I would use it. I simply felt it was “good,” so I collected several sheets at home.

At first, I used washi only in small portions, as an accent — pasting pieces, applying color over them, or using their textures. That was the natural beginning.

Japanese motifs such as Mount Fuji or dragons harmonize beautifully with washi. Painting with it felt right, adding depth to the work.

Even now, I use washi in my current projects. I’m creating a piece for a public exhibition organized by a local government to promote washi. Since the requirement was “to use washi,” this time it has become the main material.

It’s not that I feel an overwhelming need to use it, but rather, “It’s interesting, so why not?” The texture, the translucency, the tactile quality — as a material, it continues to inspire me.

Part 3: “The Shape I Will Paint From Now On” — A Place Where Art, Work, and Life Intertwine

1. Reconstructing Work and Life: Twenty Years of Work and a Growing Discomfort — “If I Continue Like This, I’ll Regret It”

I’ve been working in the same field for nearly twenty years, but lately it has been draining my energy. More and more, I feel, “This isn’t the way I want to live.”

Up until now, I’ve invested a lot in myself, but because of the nature of my job, I rarely had opportunities to share what I had accumulated. Recently, I’ve started to want to use those experiences to help others.

As I look ahead to the second half of my life, I think — no, I feel certain — that I want to live that way.

“They say that at the end of life, people’s greatest regret isn’t ‘I wish I had made more money,’ but ‘I wish I had taken more risks.’”

When I heard that, I thought, “If I died tomorrow without ever doing what I truly wanted, I would regret it deeply.” Of course, I worry about financial stability, but the fear of regretting what I never tried is much stronger. That much, I am sure of.

So I want to live in a way that contributes to the world, using the qualities I have. That desire has become very strong in me.

2. Art × Psychological Support: A Two-Pillar Vision — “Art and Dialogue That Stay Close to People”

I’ve come to hope that I can encourage people who are lost, or who no longer know what they want to do.

For such people, I imagine offering something like counseling. And if they are interested in art, I would paint a work inspired by them. This is the vision I hold — a service combining dialogue and art.

In fact, there were two times when I became seriously ill and had to step away from work. Those were painful days, like walking endlessly through a dark tunnel.

I sometimes thought, “Why is it that no matter how hard I work, God only gives me punishment?” Feelings of unfairness and futility often filled my mind.

But looking back, I feel that because I went through those struggles, I can now understand the pain of others. That’s why I want to use those experiences not in vain, but to support someone else.

Illness isn’t just physical suffering. It also unravels the balance of the mind and shakes one’s very sense of existence. I believe there are things that only those who have experienced this can truly understand.

So if I encounter someone suffering in the same way, I want to say, “This is how I got through it.” Not by forcing encouragement or cheer, but by quietly staying close to their pain, at their pace. That’s the kind of presence I want to be.

I’ve also begun to feel more strongly about sharing Japanese culture — not so much for Japanese people, but for people overseas. Through art, I want to convey aspects of Japanese spirituality, including the presence of the “dragon.”

So within me now, there are two axes: “Art for abroad” and “Counseling for people in Japan.” I haven’t taken concrete steps yet, but the vision is already clear in my mind.

3. Words and Awareness: The Power of Dialogue — “From a Person’s Words, the Landscape of Their Heart Appears”

For me, painting is one means of expression, but at the center is always people.

For example, setting aside the paintings themselves, through conversation — perhaps thanks to my background in NLP — I’ve come to believe deeply in the power of questions.

How you ask, and how the other person answers — I feel their psychological state is revealed entirely in those words.

It’s often said that “feelings are invisible,” but I believe words themselves are feelings. People don’t all use the same words. Each person’s unique choice of words, filtered through their own perspective, reveals the state of their heart.

Of course, there is the academic side, but in addition, I have a more intuitive, almost spiritual sensitivity that makes me connect with people easily. Perhaps I see people more clearly than most.

That is also why art becomes a natural medium for me. In my case, the chosen means happens to be painting. But if someone had no interest in art, perhaps the dialogue would end with words alone.

I’m not bound to painting itself. At the root is “people” — staying close to their words and feelings. That, I believe, is my true theme. And I think I will continue painting it for the rest of my life.

If you’d like to read the original text in Japanese, please click below